I’m what you call a real collage.

I never underestimate one’s appearance because you project something.

I always had a flair for clothes and liked them

because I have a whole feeling about appearance. Because I think you very carefully can

identify a person by their appearance. It's

important. It's not skin deep. It's much deeper. And consequently in youth I had this kind of

flamboyance and wore good clothes and wore attractive things. So I think it was taken for granted that a

woman of that sort couldn't be totally dedicated. So I think that because of their, not mine,

their preconceived ideas that an artist had to look -- that the older and the

uglier they looked, the more they were convinced that there was a

dedication. Well, that again is

preconceived clichés. That's what I've

been trying to break down all my life.

And I still am.

Because,

you see, again what probably has given me my vision is that I have not been

caught in clichés. When I was

growing up, it was fashionable if you were pretty to say, "Well, beauty is

skin deep." Well, beauty is not

skin deep. Beauty is beauty. In other words, I would like to say that the

whole thing that we're talking about has one note in my life, as you can

see. And that is the important thing to

me. Now, another thing. Let us take Beethoven, just because everyone

knows Beethoven. And we're talking about

his time and in the Occidental world.

Now in music we have octaves and there are eight notes and then some

half notes. And out of eight notes he

built a world of sound. All the things

that he created are really out of eight notes.

Now those eight notes go higher, an octave higher, an octave lower. But there are only eight notes in an

octave. Now I need only one note. And that is my note of consciousness. And that is what I want more of: my own

consciousness. Louise Nevelson, Archives of American Art.

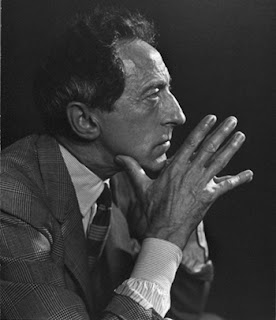

Could there be a more forceful statement than this about the relationship between mind and beauty? I was aware of Nevelson's striking appearance and had seen many of her sculptures, but knew nothing about her bold statements about dress. She espouses an unabashed credo lambasting all those who think that an interest dress is superficial. I love the top photo by Richard Avedon: it embodies perfectly her statement about being a "real visual collage" with her elaborate hat, bold sculptural necklaces and intricate pieces of clothing.

Could there be a more forceful statement than this about the relationship between mind and beauty? I was aware of Nevelson's striking appearance and had seen many of her sculptures, but knew nothing about her bold statements about dress. She espouses an unabashed credo lambasting all those who think that an interest dress is superficial. I love the top photo by Richard Avedon: it embodies perfectly her statement about being a "real visual collage" with her elaborate hat, bold sculptural necklaces and intricate pieces of clothing.